Aspen Lake team and resident defy ‘experts’ who said wounds would never heal

By Kristian Partington

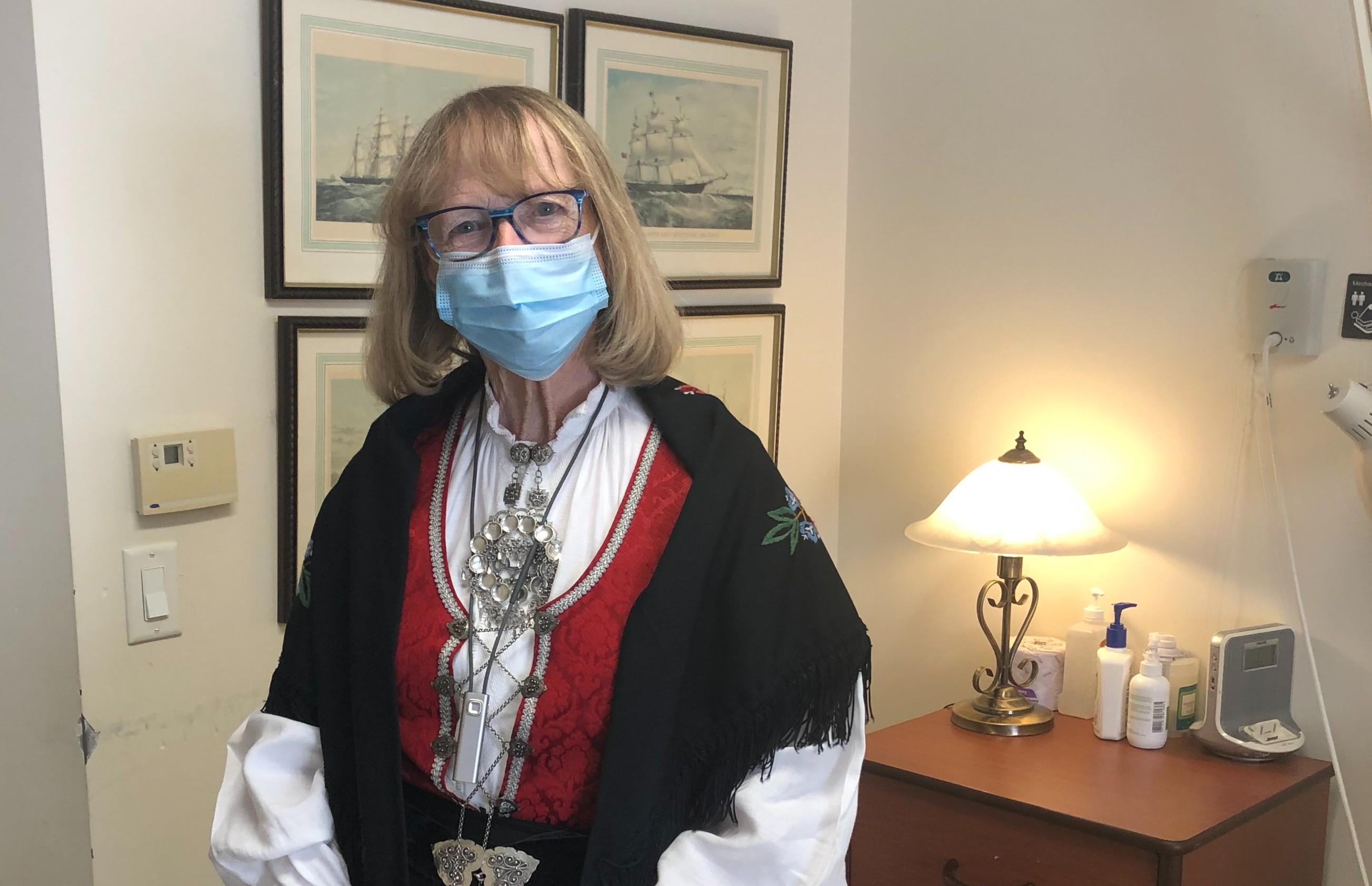

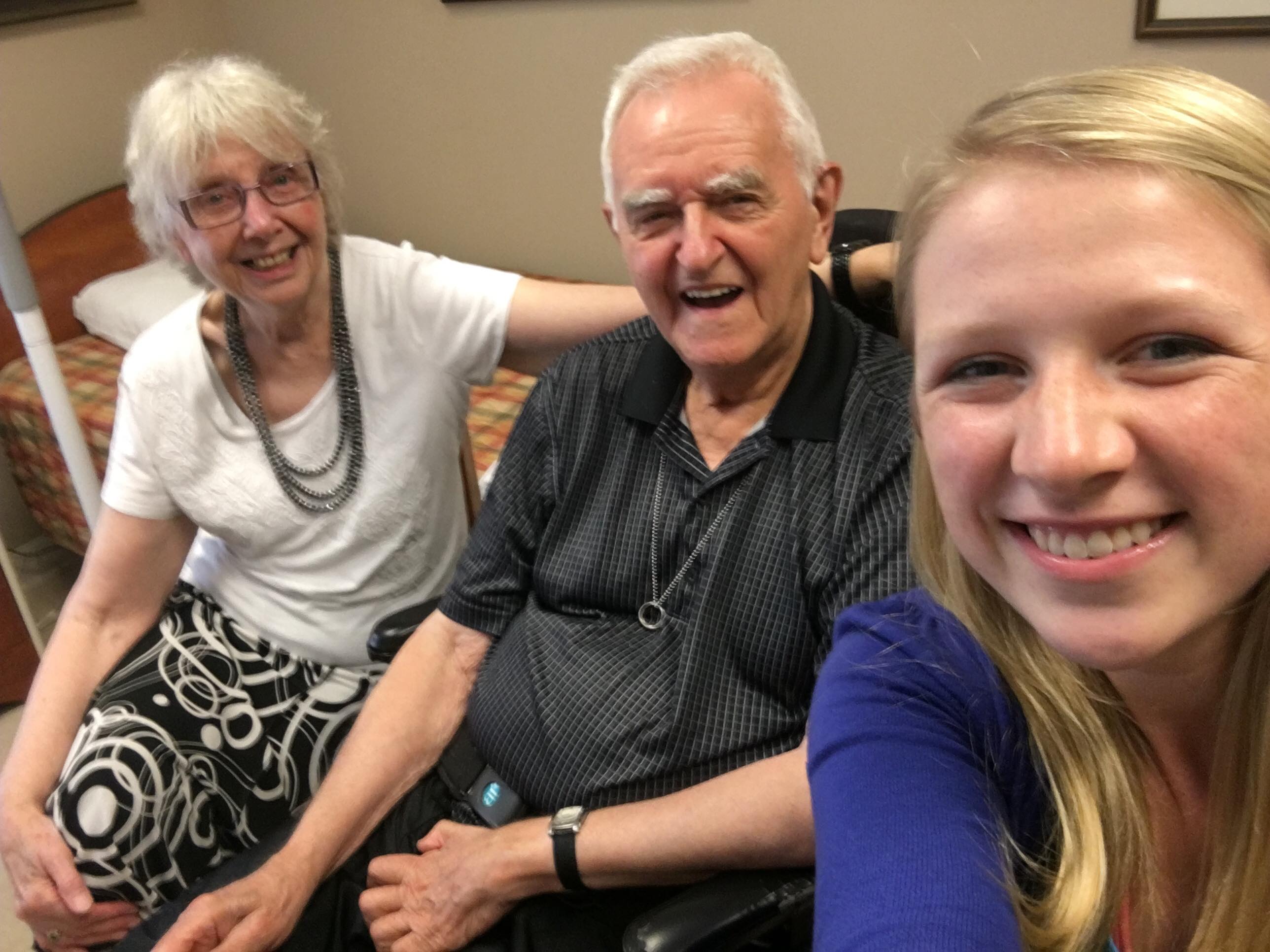

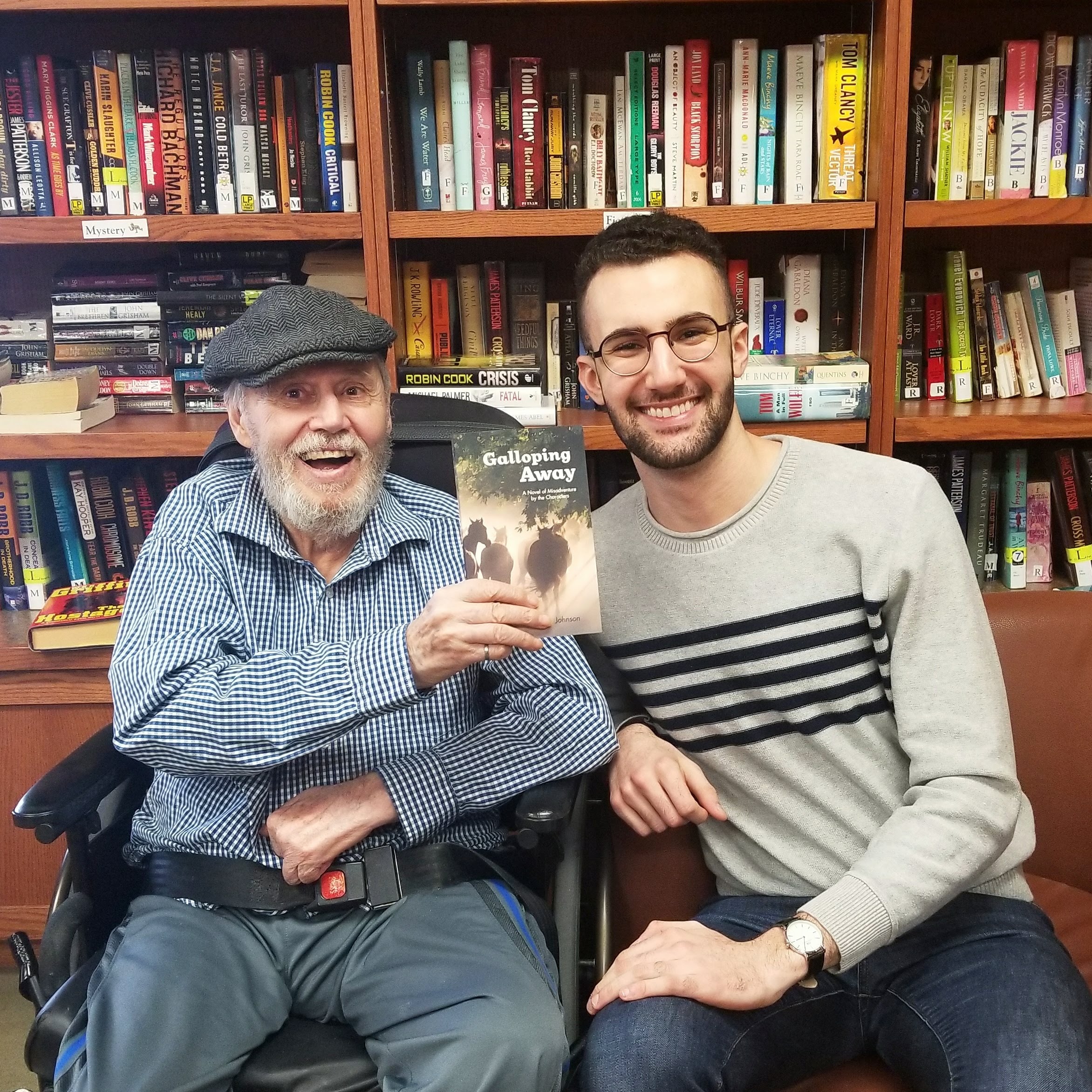

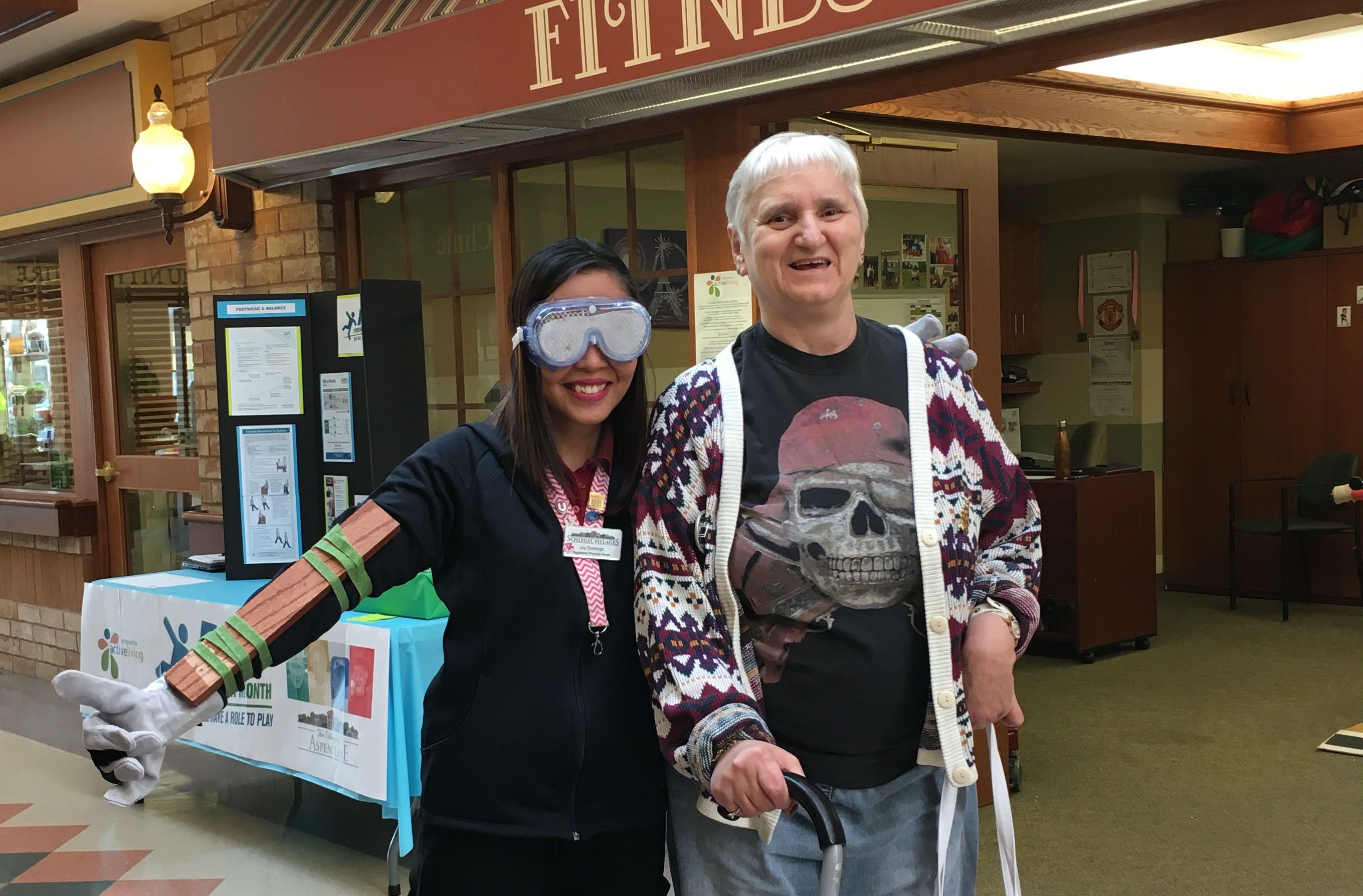

When Patricia Perron first moved to the Village of Aspen Lake from a complex care home in Windsor nearly four years ago, her care plan suggested that the severity of the three stage-four pressure wounds she was living with was virtually irreversible.

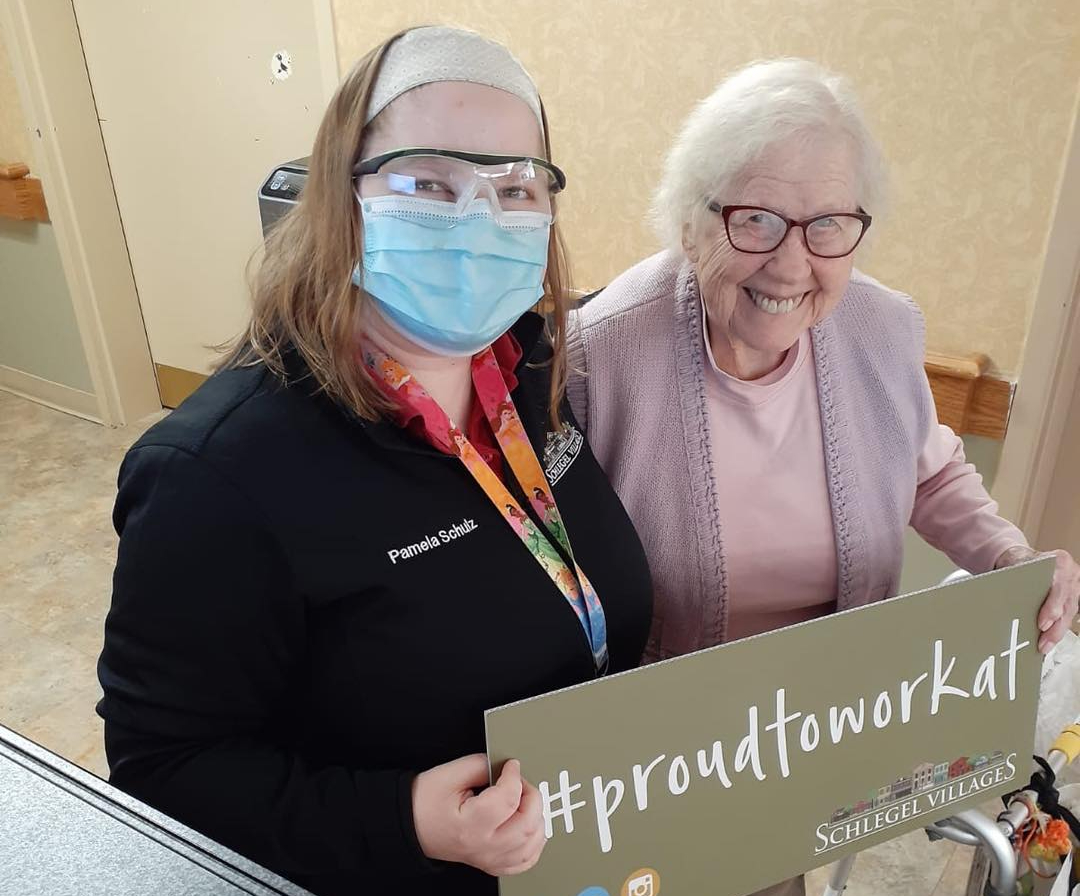

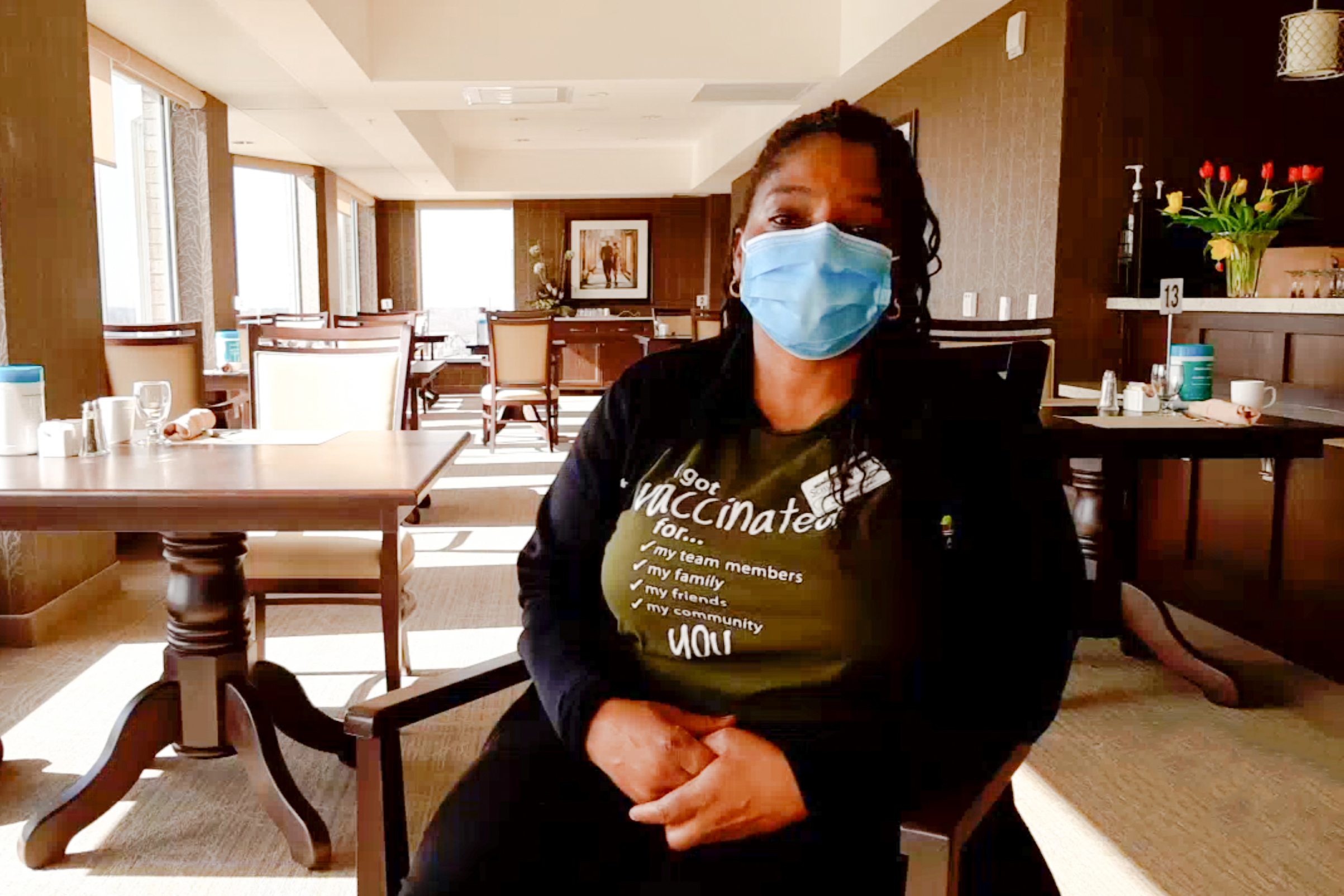

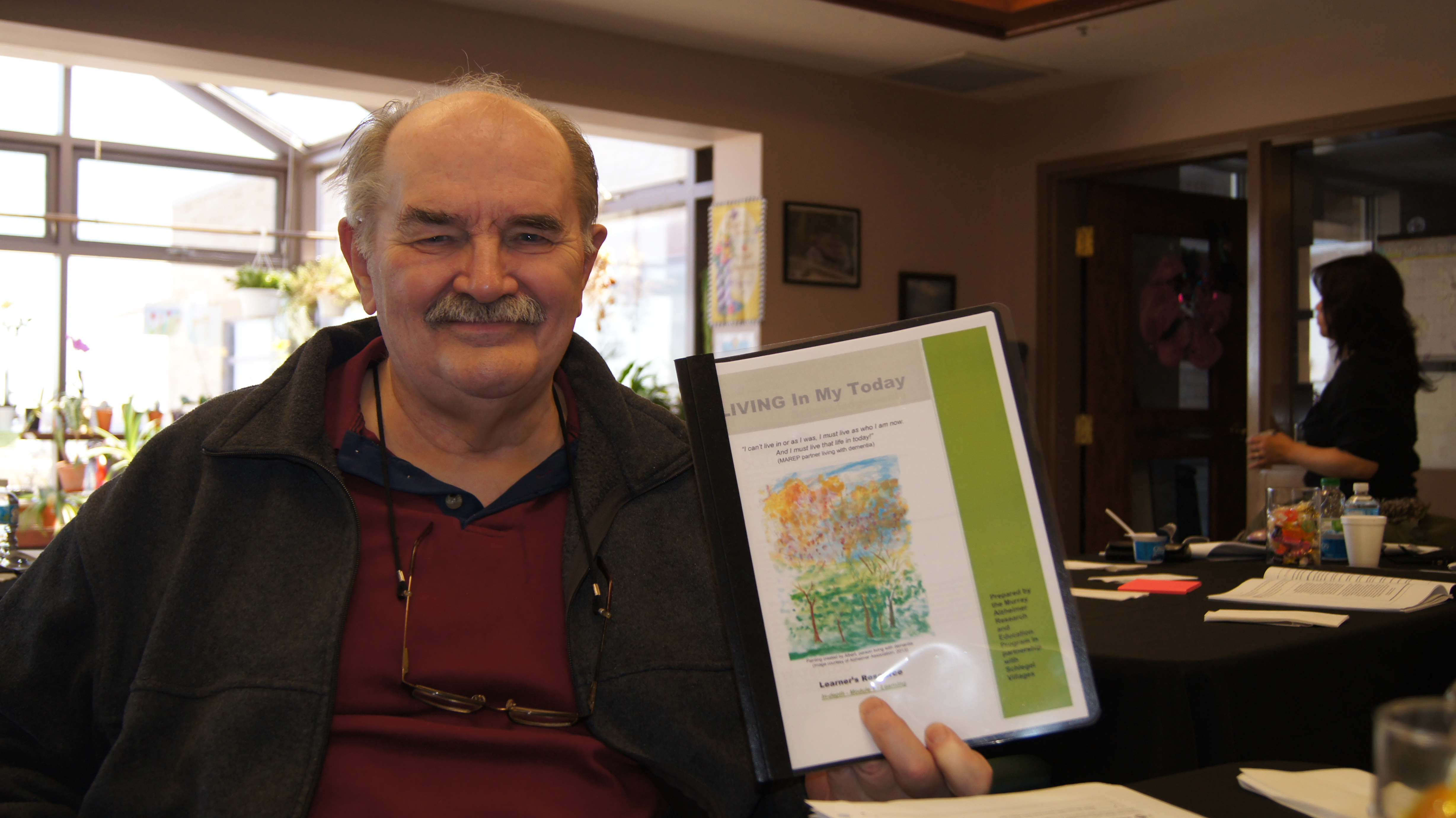

The depth of these wounds went to the bone, says Kim Arquette, who as a nurse was inexperienced in wound care at the time. “We were told when she came here that those wounds would never heal,” Kim says. The previous care providers had made no progress in two years, and they said progress was impossible. Pam Wiebe, now the General Manager at Schlegel Village’s Coleman Care Centre in Barrie, was at Aspen Lake in those early days after opening, sharing her nursing expertise with Kim and fellow team members. That’s when Kim was first exposed to the intricacies of specialized wound care, and despite what outside medical professionals said, with Pam’s support and the knowledge she gained in additional training, Kim was determined to heal Pat’s wounds.

“We healed the very last one about a month ago,” she says with a smile during a short gap between resident visits on a cold November morning. The team and Pat had a small celebration that day, and though Pat remains quite frail and requires a lot of support, the quality of her life continues to improve daily.

Getting to this point took a combined effort from the neighbourhood team that works closely with Pat every day. It would have been easier to accept those early “expert” opinions and simply manage the wounds, Kim admits, but through Pat’s experience she believes much can be learned about the connectivity between emotional, mental and physical well being. Team members saw it first hand, and the smile that comes across Pat’s face when discussing the connections she has with those who care for her is evidence of her betterment.

“I recognize that her quality of life has improved just through her smiles, which were lost behind a blank look for many, many months,” Kim says, noting that Pat slipped into a serious depression about a year after moving into the village, presenting a major barrier to the healing process. She wouldn’t leave her room or socialize at all; she didn’t even want to get out of bed. In the dark of her room, 24-hours a day, her worsening physical wounds compounded upon her emotional ones and that’s when a breakthrough finally came.

“This is what defines you as a nurse, a practitionner or a health care provider,” she remembers saying to fellow team members as they discussed Pat’s decline. “It’s this moment that defines who you are; those are the moments that you have to be proactive and say ‘you know what, we recognize that you are sad, we recognize that you aren’t feeling good, but we’re here to help you and we care.’ ”

First, a greater sense of trust began to form between Pat and the team, and friendship followed. These growing relationships gave her a new reason to want to get out of bed, and her depression seemed to lessen. She began to come out of her room for meals – first one a day, then two, then three. Her blood circulation improved, she was getting more sunlight and oxygenation, and her wounds showed signs of improvement.

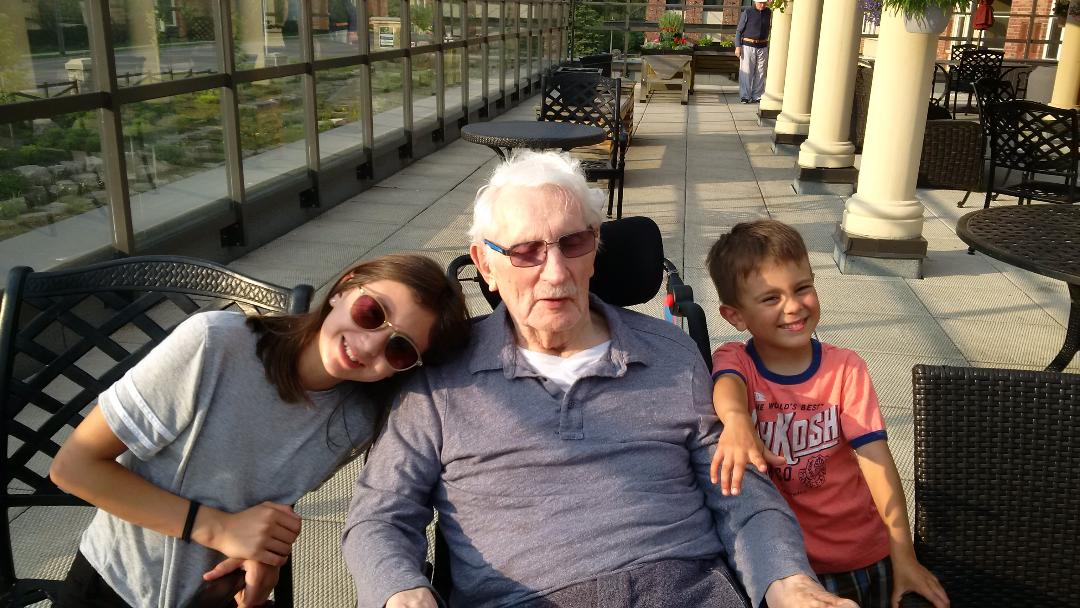

“We can’t ever forget the power of the mind and the psyche that plays a part in healing,” Kim says. “The mind, body and the spirit all go together, and sometimes people forget that.” Today, Pat is like an adopted Grandmother to many of the team members’ children, and she loves to hear about their lives. Kim takes Pat by the hand and tells her how well she’s looking on this morning, and Pat smiles up at her. It’s a smile Kim and the team waited a long time to see. The next time someone tells them a wound can never be healed, that’s the smile they’ll think of.

- Previous

- View All News

- Next