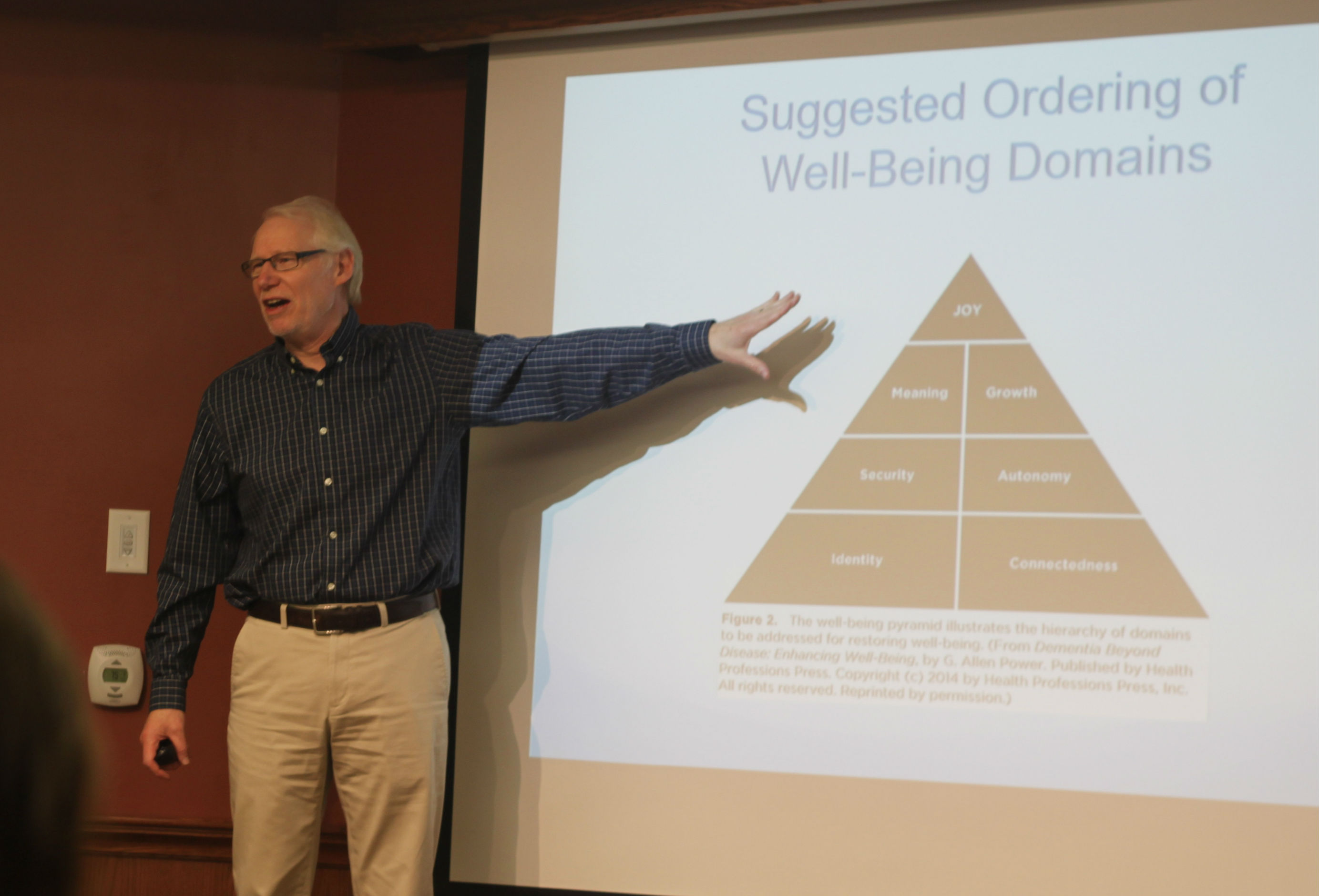

This is the third story in a series related to the concept of the seven domains of well-being and the idea that if a person is lacking in either security, joy, meaning, growth, connectedness, autonomy or identity, then their prospects for quality in their life are greatly diminished. For people living with dementia or mental health challenges, this diminished sense of well-being in any of the domains can result in words, gestures, actions or reactions that can be difficult for caregivers and loved ones to respond to. These personal expressions all have meaning and in many cases they are ways of communicating unmet needs or a person’s lack of well-being.

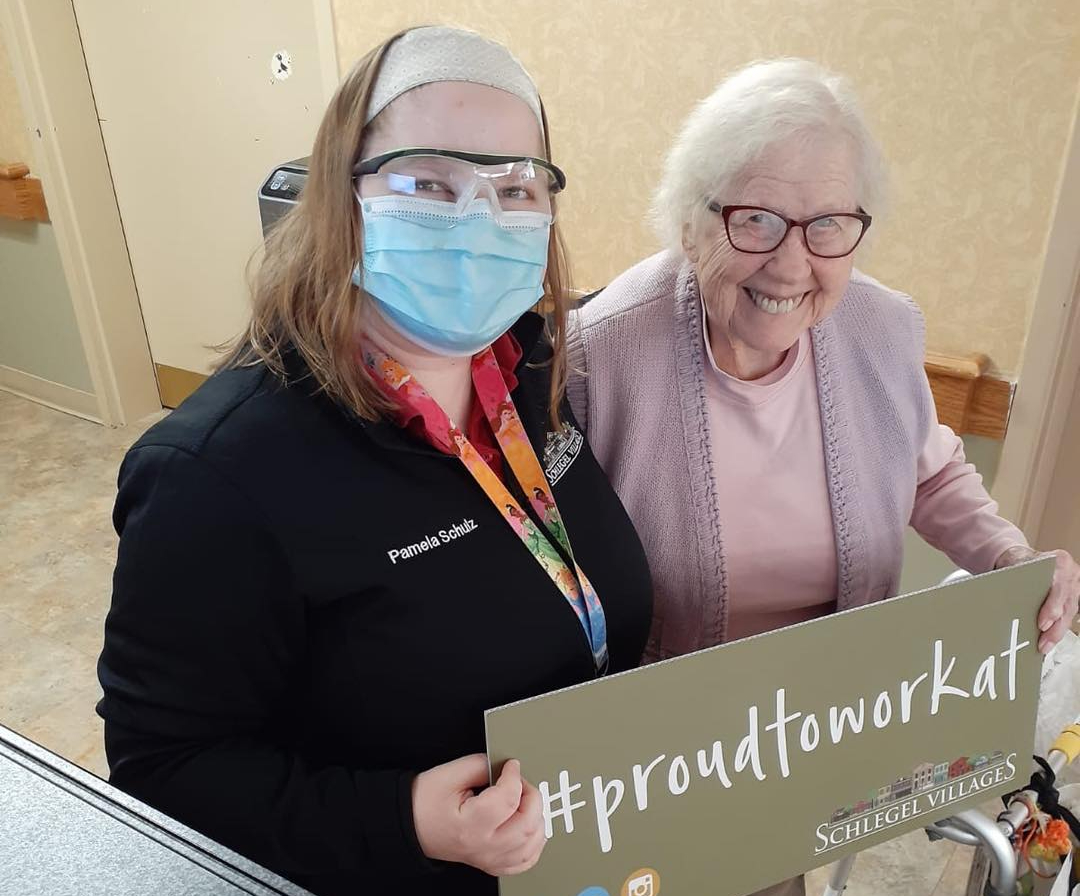

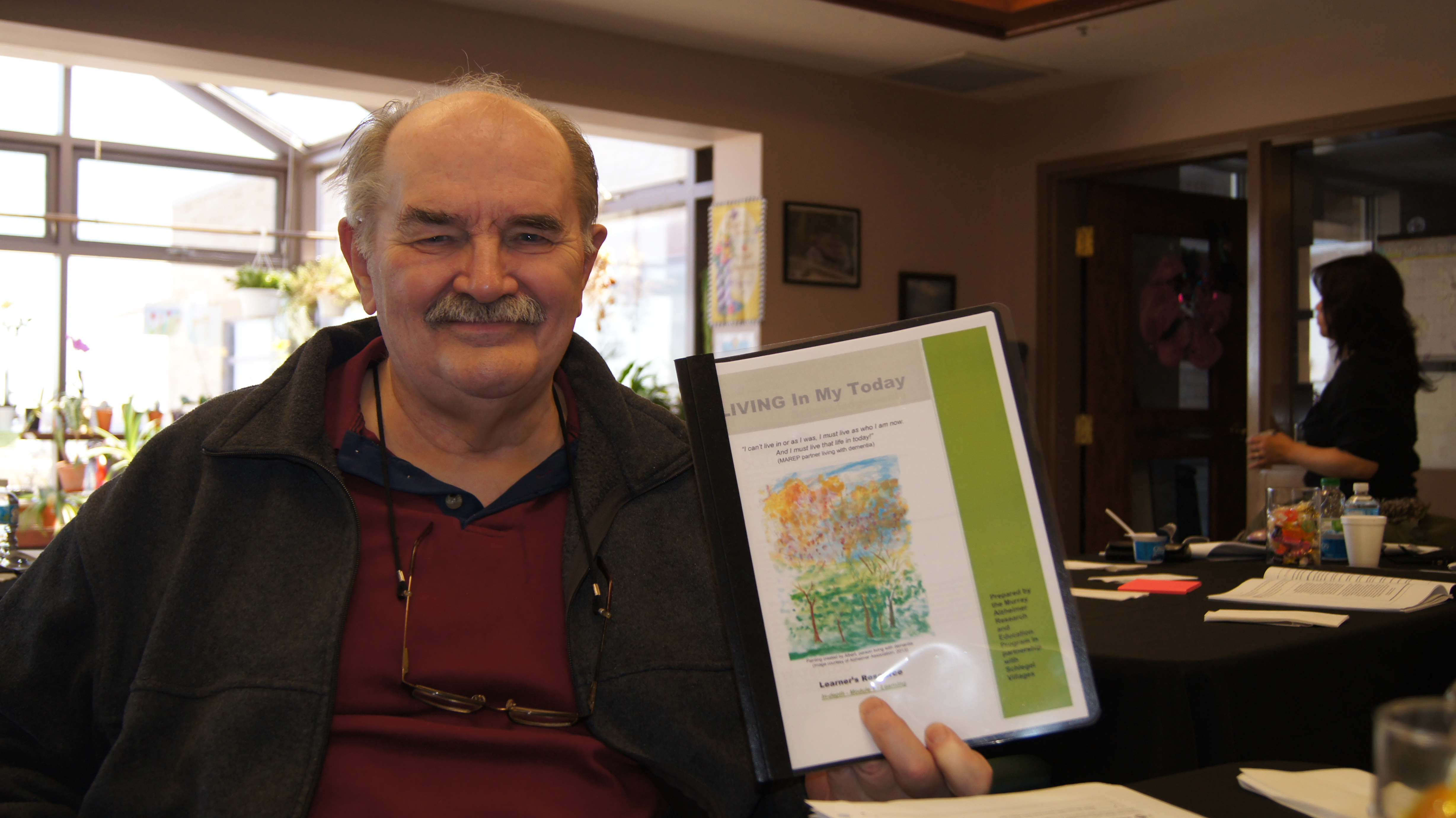

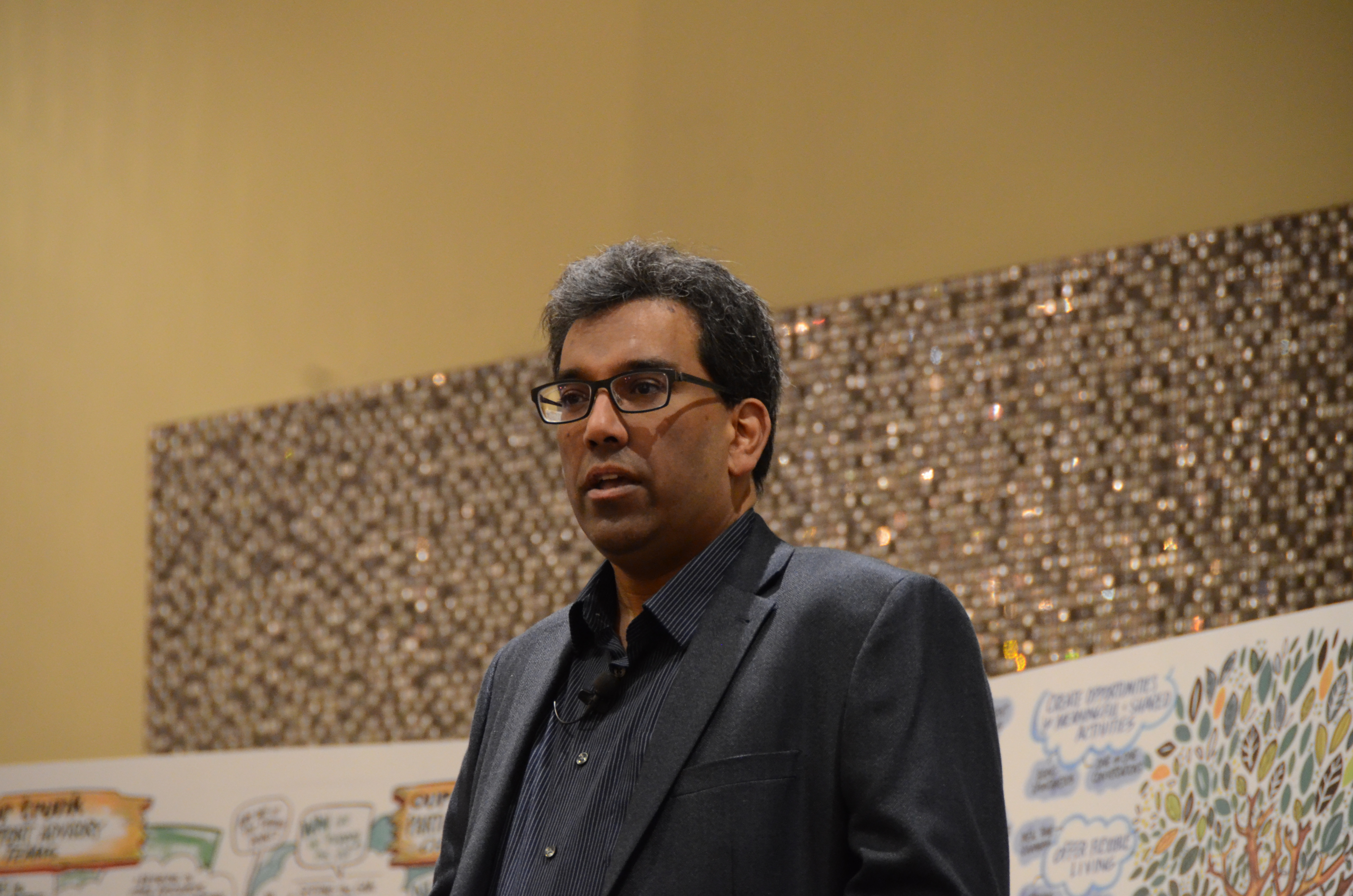

With the support of Dr. Al Power, Schlegel Chair in Aging and Dementia Innovation with the Schlegel-UW Research Institute for Aging, and Personal Expressions Resource Teams (PERT) throughout The Villages, care partners are beginning to understand how to use the seven domains of well-being to support residents.

Click here for the first story in this latest series, click here for the second and click here to read more about when this idea was first introduced at Schlegel Villages.

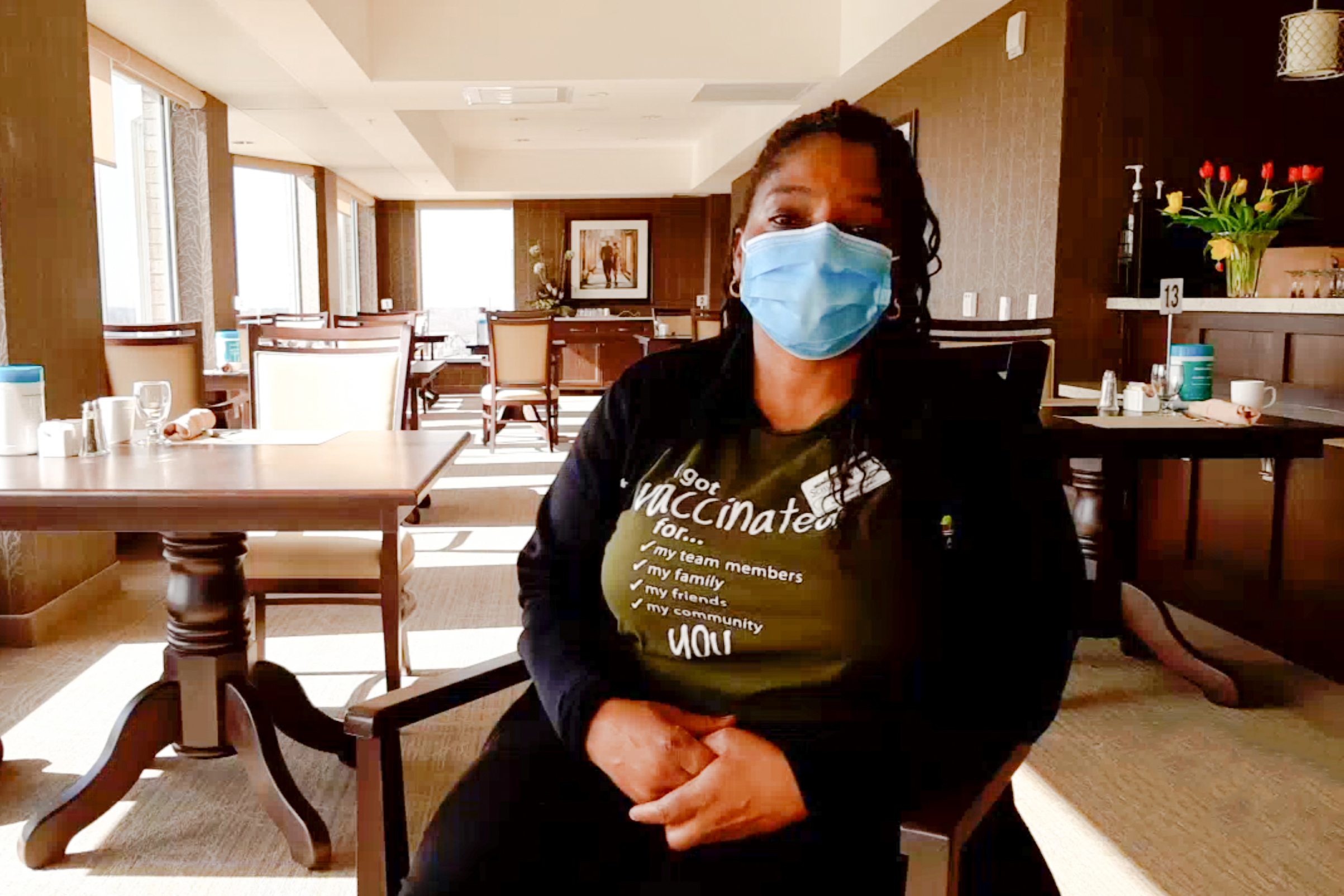

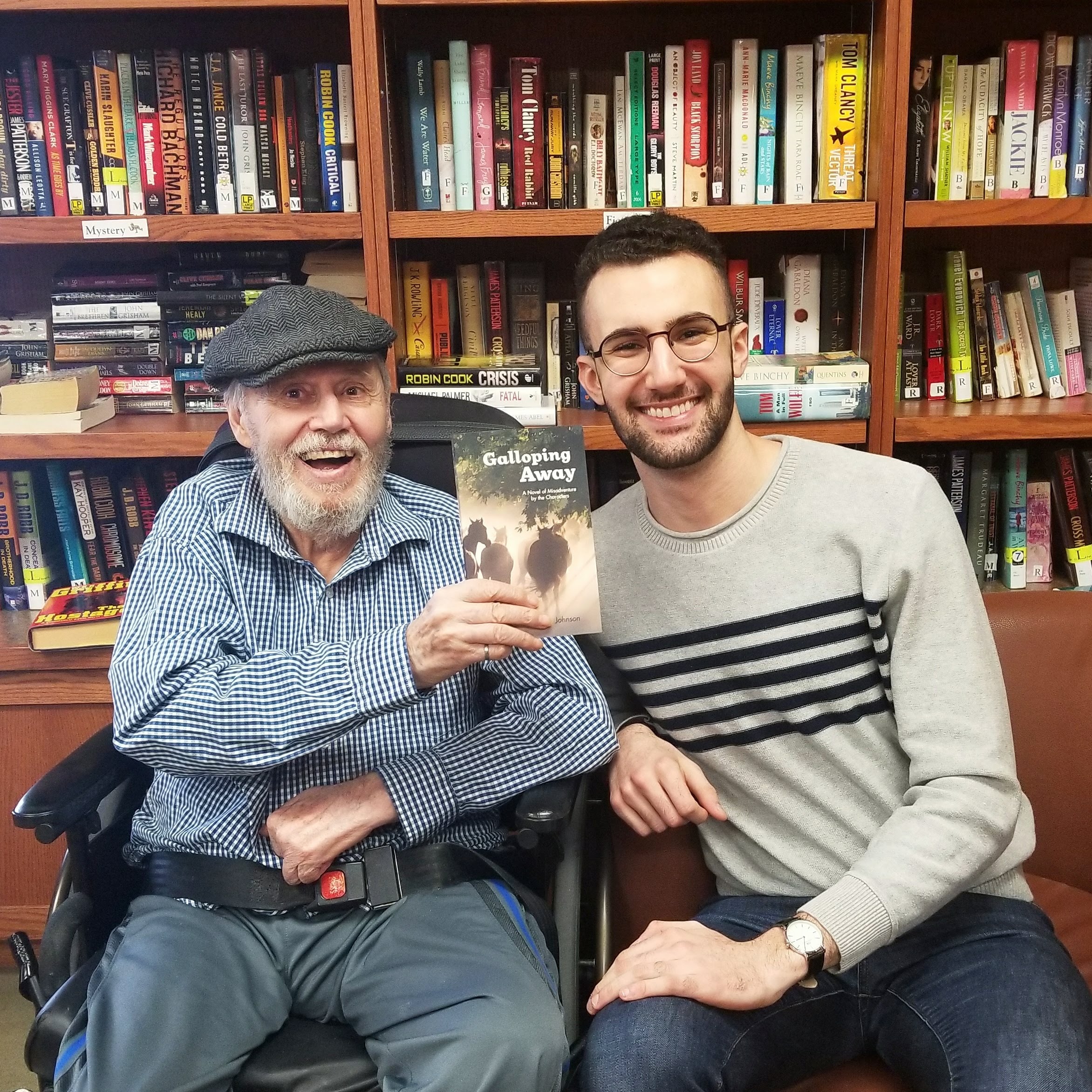

Erica Hooker is a Neighbourhood Coordinator at the Village of Aspen Lake in Windsor, and the Village’s PERT lead. During the annual Schlegel Villages/RIA innovation summit in June, she shared the story of a resident we’ll call Carl and how in the summer of 2017 the team used a bit of a different approach to support him with the seven domains of well-being as their foundation.

Carl has lived in the village since it first opened in 2011. Overall, he’s a sad person who has lived a long life in the shadow of early childhood trauma. He coped with alcohol and other substance abuse and left behind him a string of broken relationships. Bipolar disorder, the aftermath of his substance abuse and the onset of dementia carried him to Aspen Lake, and a diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease followed.

The care for Carl was almost strictly clinical for the longest time – pills and medications were the answer to his problems, the doctors urged, and yet his personal expressions grew ever more challenging. Social workers, geriatric mental health outreach and respected specialists were all brought in to support Carl, and “he was not willing to accept that help and accept the baggage that he was carrying,” Erica explains. He began to clash with other residents and with team members, and some began to feel his personal expressions were manipulative and hurtful.

It was a difficult time for everyone involved.

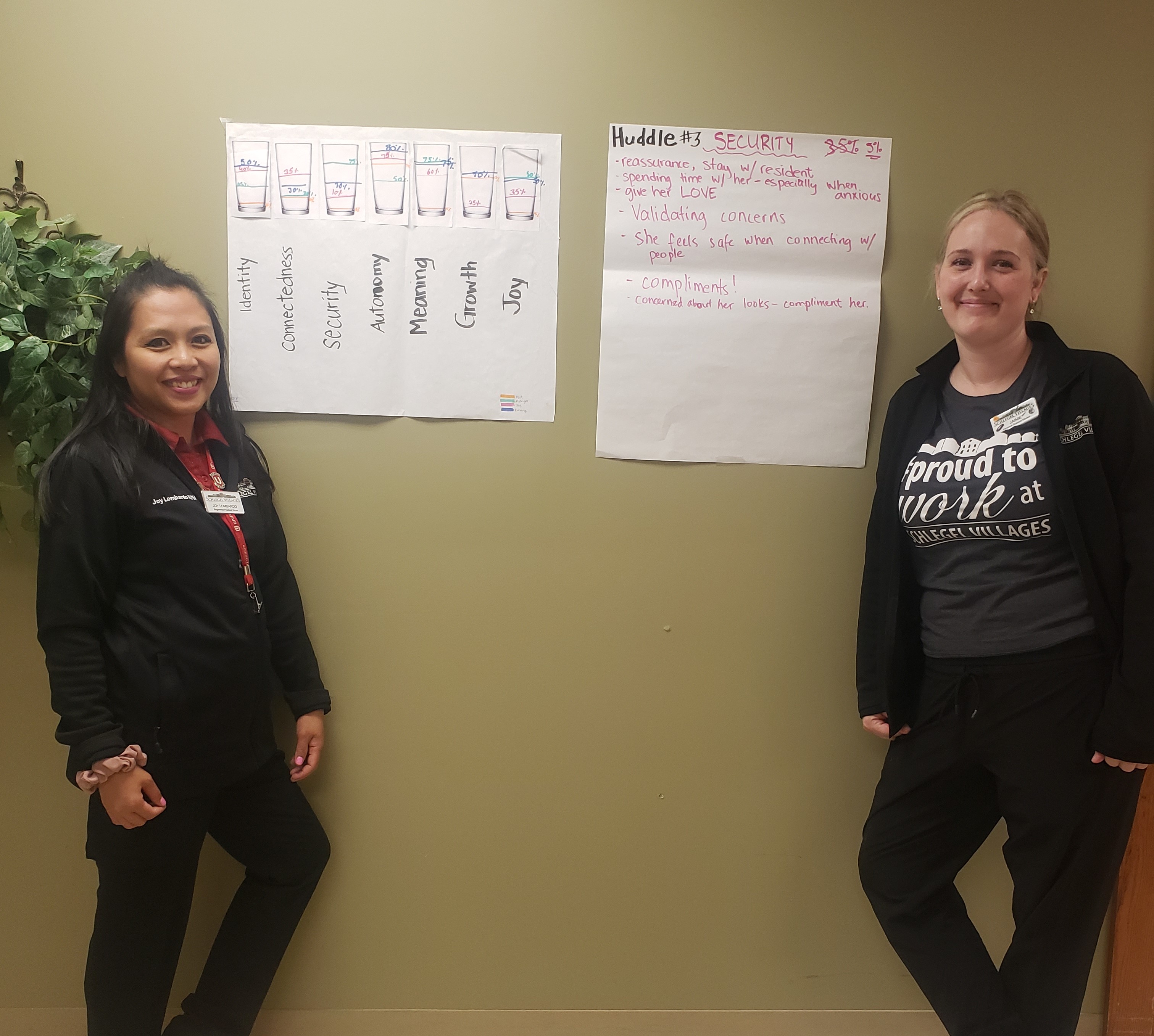

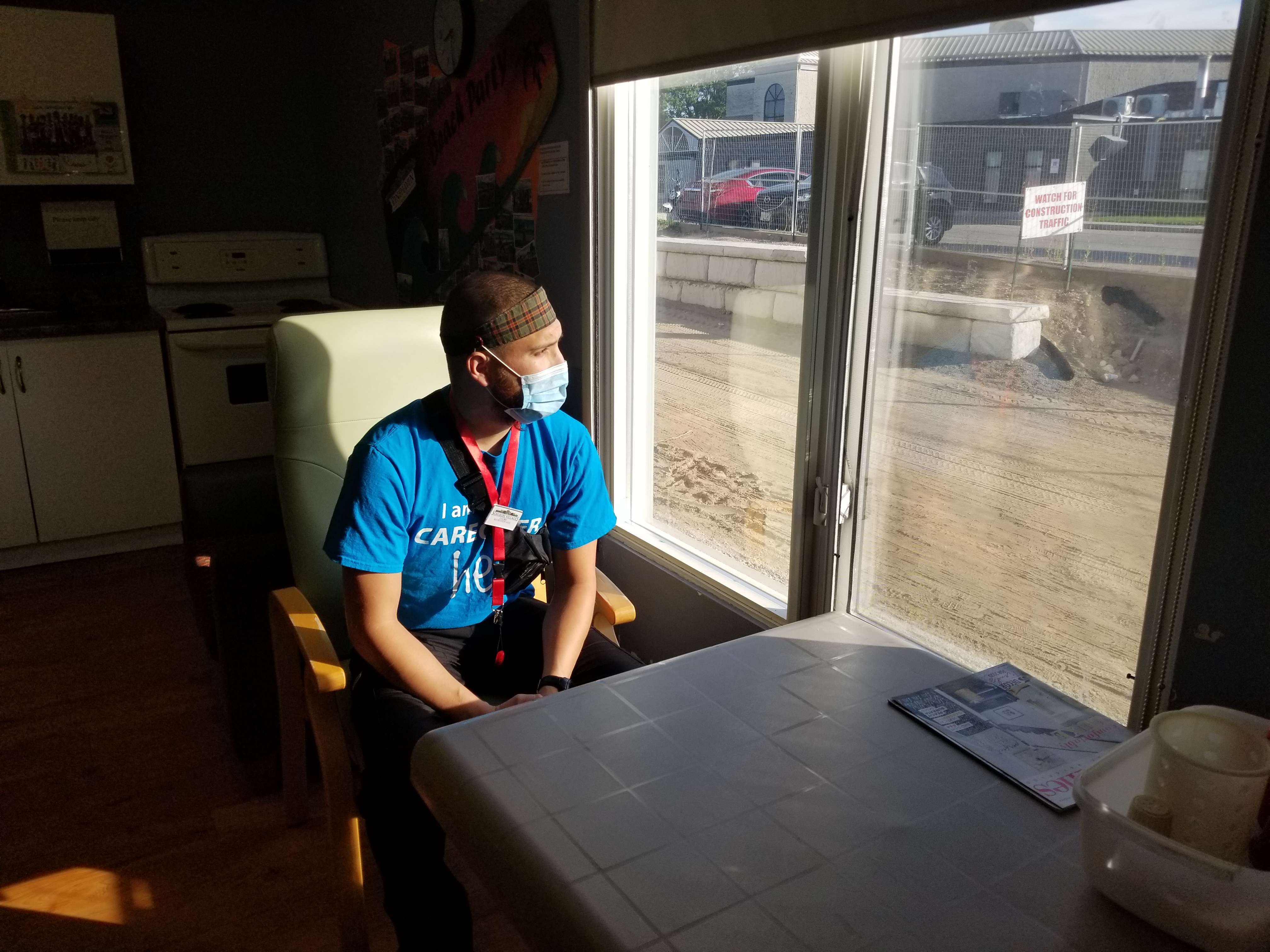

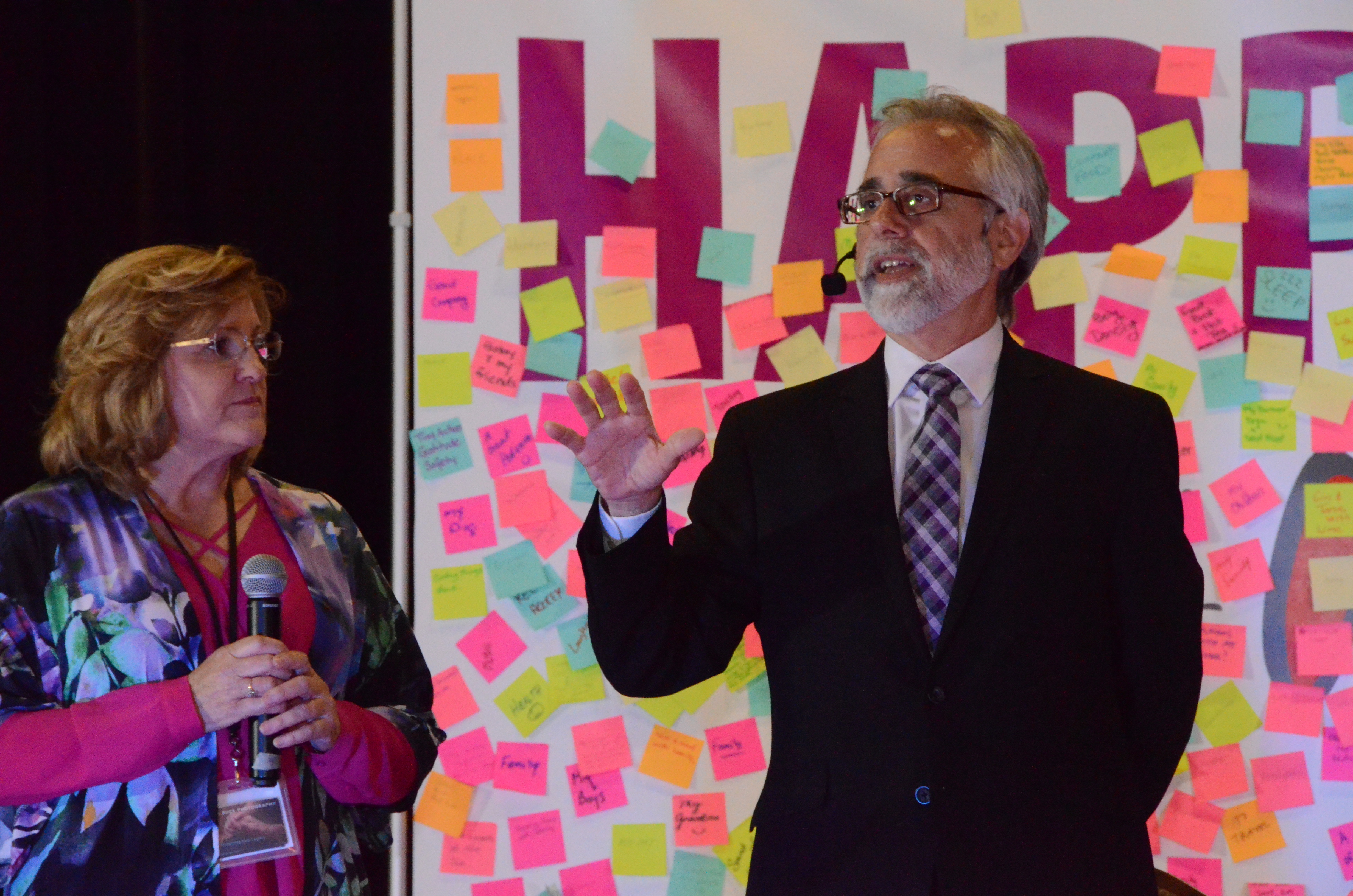

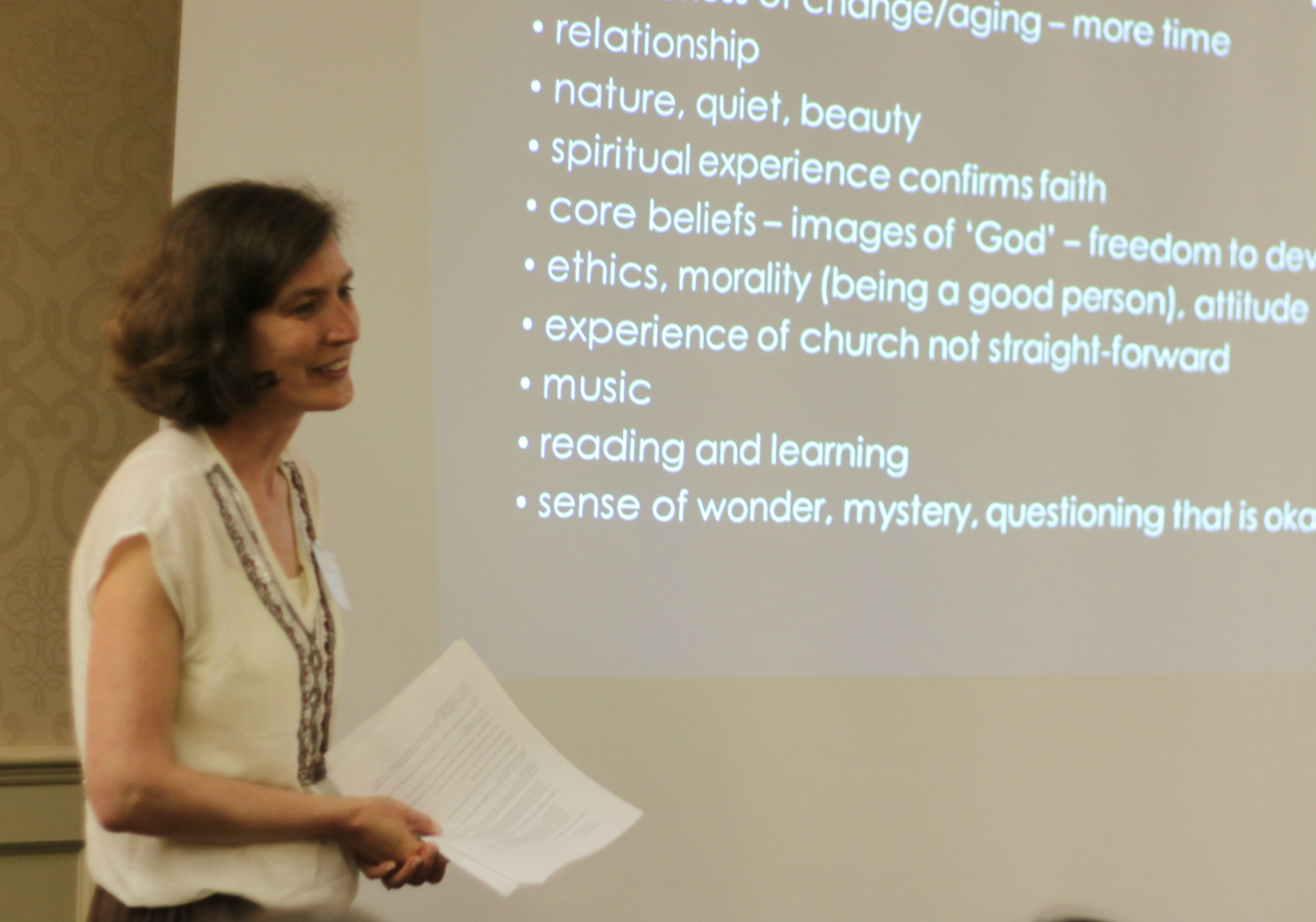

Then an opportunity came to bring all 12 people with the PERT teams of Aspen Lake and neighbouring St. Clair together, as well as nurse consultant Melanie Pereira from Schlegel Villages support office, who works with all PERT teams across the organization. She suggested they “do the cups,” where the team splits into seven groups, each focused on one domain of well-being, and they discuss how full Carl’s cup is in their specific domain.

Each domain was quite low, practically empty.

“Seeing that was very eye-opening, to say the least,” she says. “He has no security,” she remembers thinking at the time. “He has no autonomy. How could he possibly right now feel like there’s any kind of growth?”

They decided to take the same exercise to the team that supports him directly in his neighbourhood, and one team member, who has a strong relationship with Carl, did the cup exercise with him. The team was surprised to learn that he felt his cups were, at minimum, half full, while some were as high as 75 per cent. The team had commented on why they thought his cups were empty while he also offered his explanation as to why he throught they were actually quite full, and the comments were posted together for the team to see.

“It was so impactful for the team to see in a positive way that he was feeling better than we thought he was feeling,” Erica says. In one of his comments, however, he mentioned how he sometimes rings his call bell in the middle of the night, and when a team member arrives, he’s often forgotten what his concern was. He felt bad about this, and worried the team members thought he was “crying wolf.” When the team saw this, they could empathize.

“I’m so screwed up in the head,” he finally told the team member as they were wrapping up their discussion, “and I know it.”

The team had to come to terms with the fact that every expression has meaning. “It doesn’t matter if it’s mental health, it doesn’t matter what it is, it’s not directed at you as a care provider,” Erica says. “There is a background, a history, and unfortunately in that moment in time, you’re the outlet.”

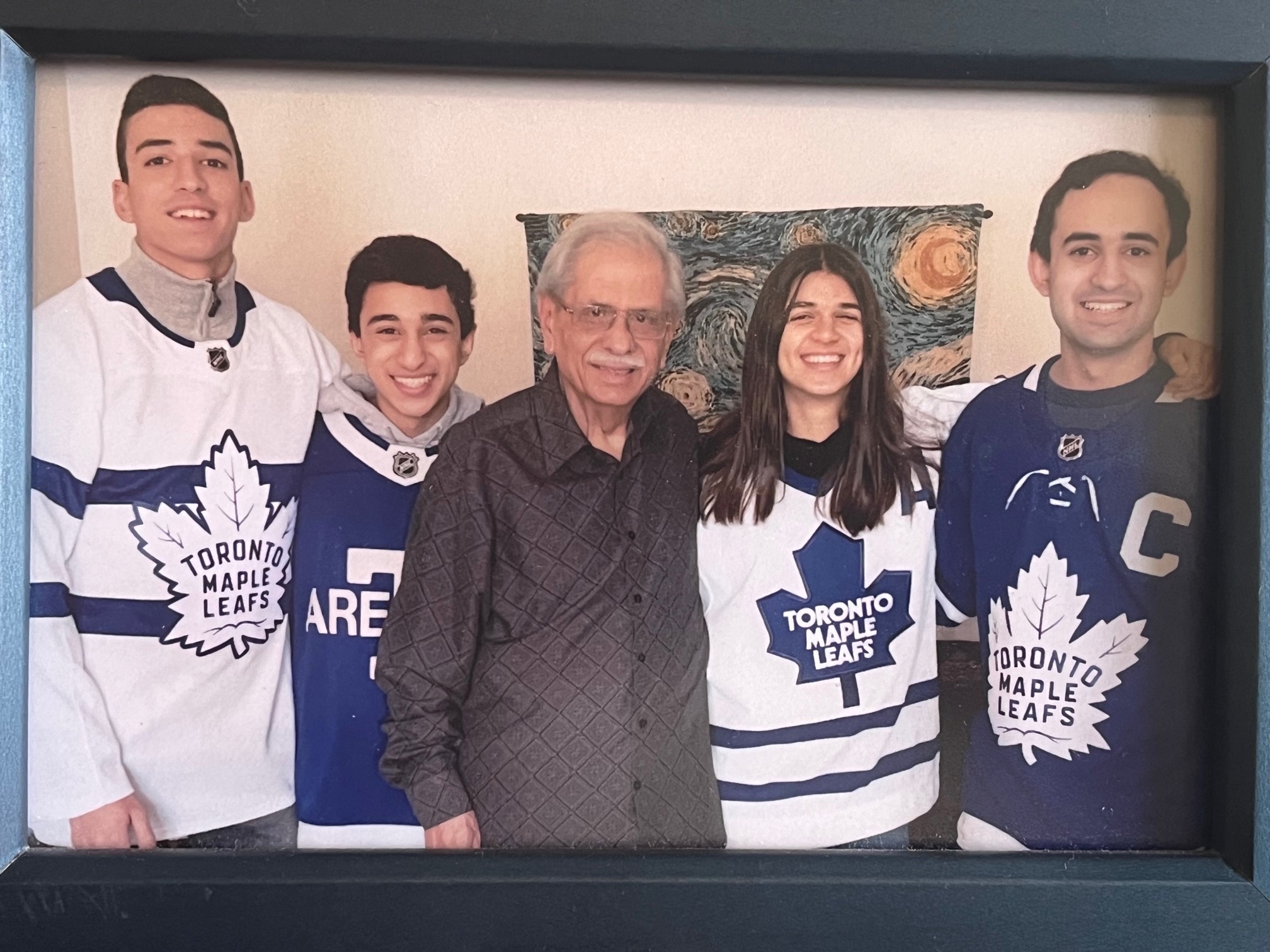

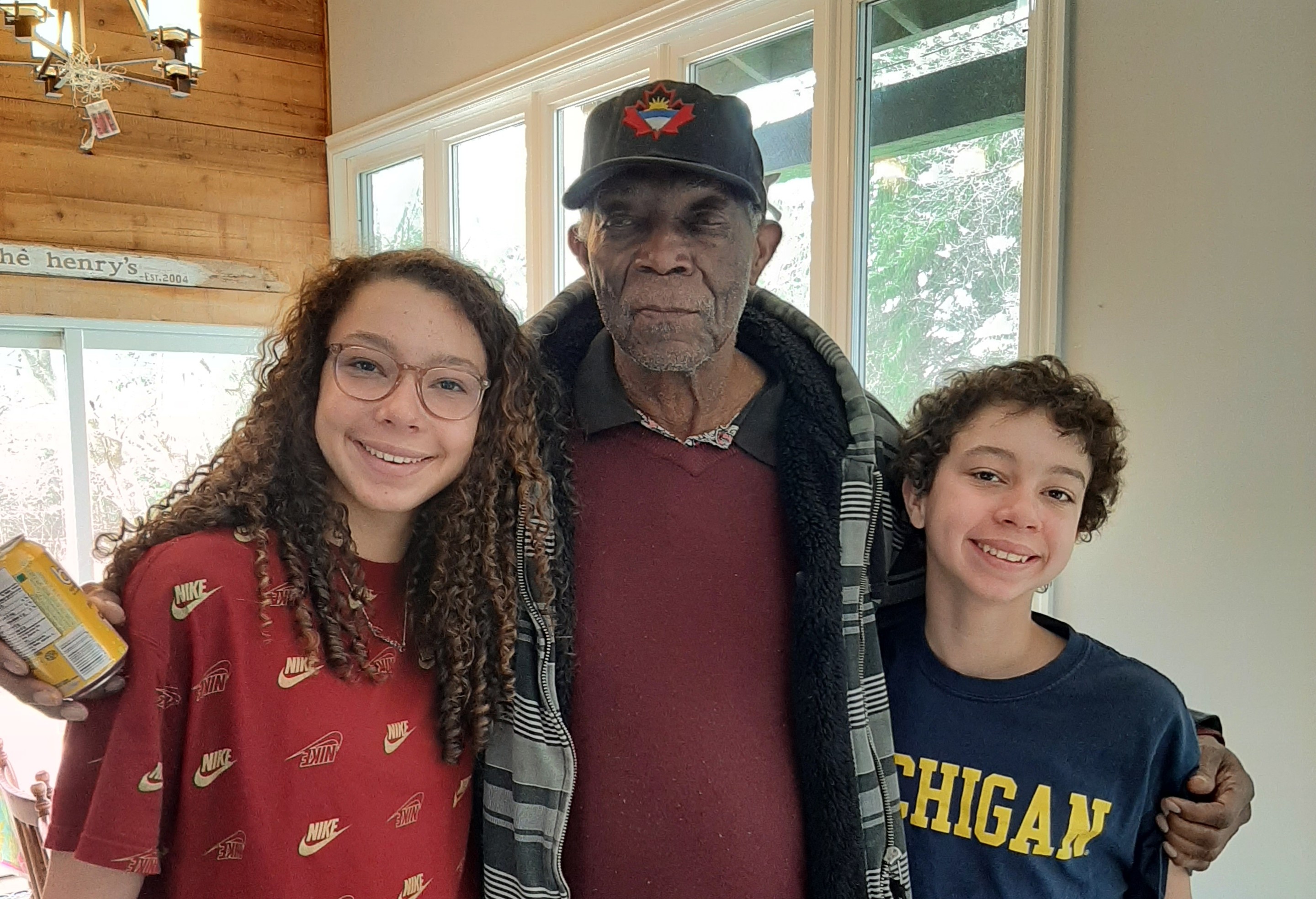

A year after this experience with Carl, Erica says he’s doing quite well. His daughter, who hadn’t seen in a few years, reconnected with him and he’s seeing his grandchildren from time to time. Erica spoke to him just before leaving for the Innovation Summit, and he told her how much he loves his grandchildren.

“The one thing that stuck out for me,” Erica says, recalling that discussion “is he told me ‘in all of my years, the safest place I’ve ever felt is here at Aspen Lake.’ ”

Erica says there are still many days filled with challenges to overcome, but Carl has come a long way. The important piece to take away from Carl’s story, Erica says, “is that “there is no magic pill. If I’m lonely, and if I have a reason to feel it, then no Haldol or Ativan is going to fix that.”

“We have to work on well-being, for all of us.”

- Previous

- View All News

- Next