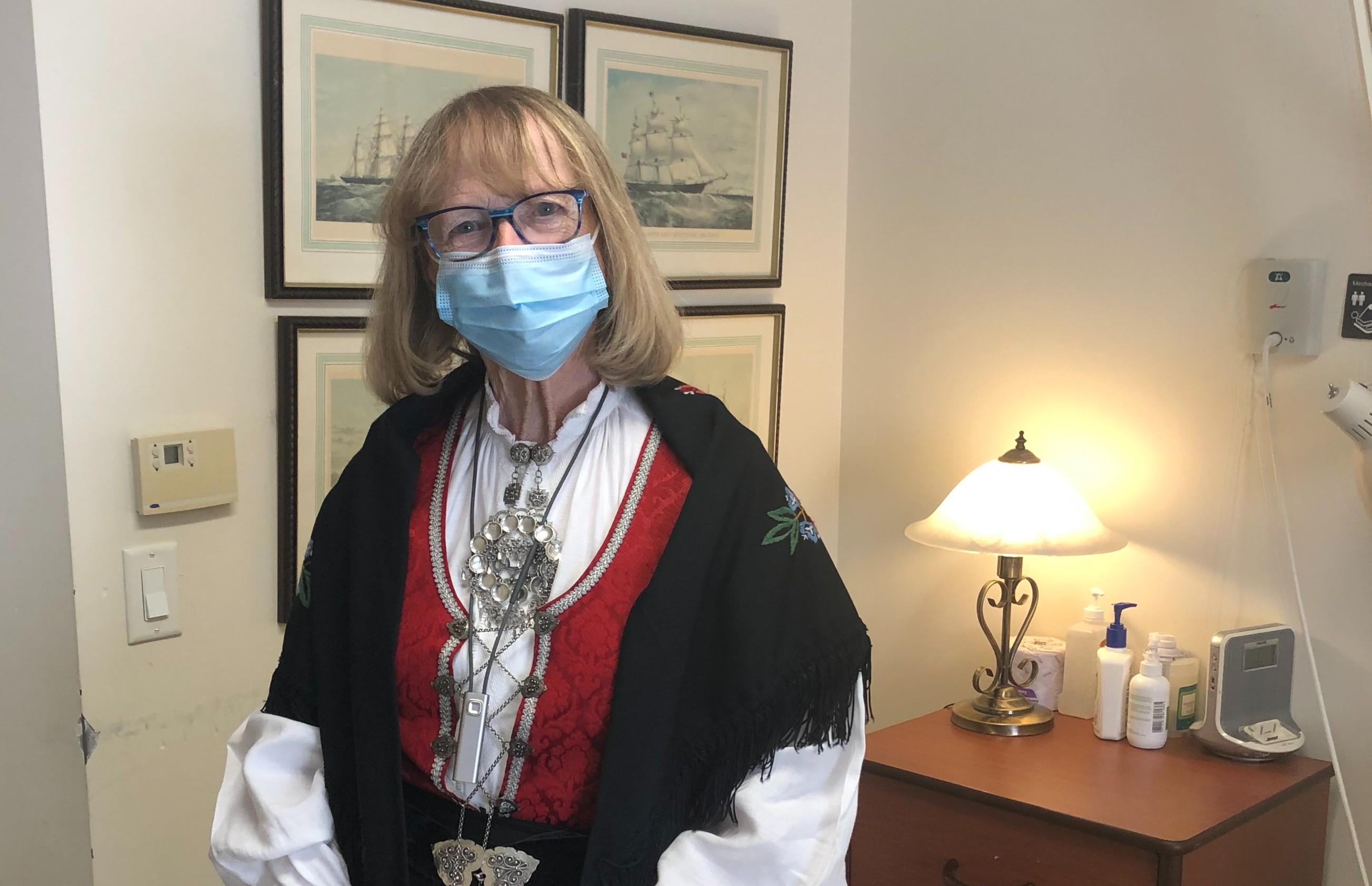

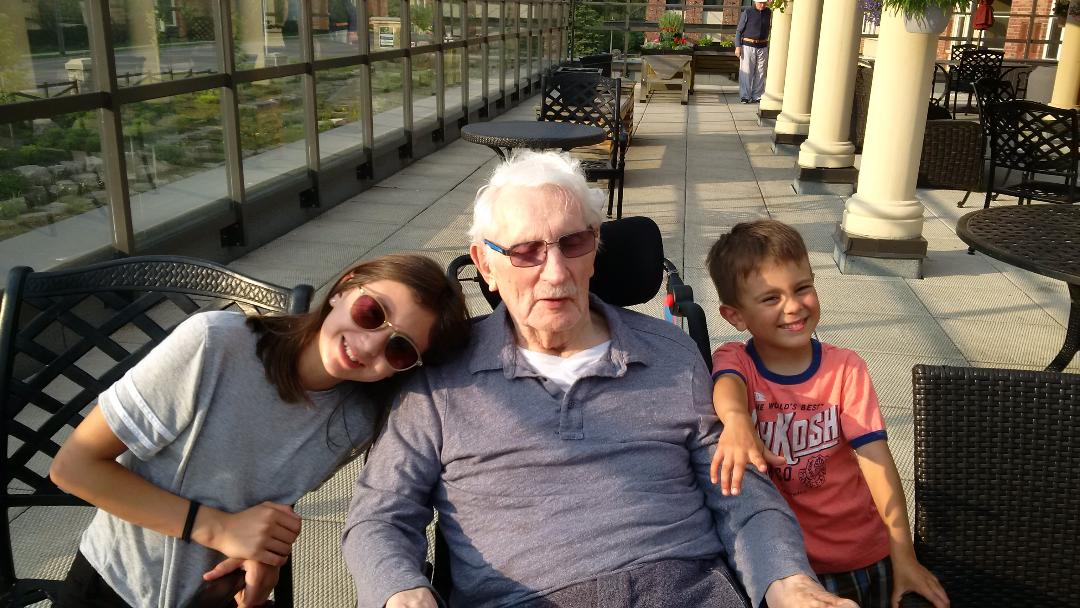

With a soft laugh and a quiet, humble voice, Ruth Watson Henderson says it has been quite a while since she’s played the piano for anyone other than herself. She then wheels herself over to the old Steinway Grand in her suite in The Village of Humber Heights, sets up before the keys and pauses a moment to reflect.

Music took Ruth all over the world, and it's still a big

part of her life at The Village of Humber Heights.

Through the conversations she’d just been having, it’s clear her short-term memory fluctuates and now it seems in this instant that she’s reaching into her memory bank to draw out a song to play.

Then her fingers start at once to dance upon the keys and the gentle notes of Mendelssohn’s Spring Song fill the room as though they are filling the cavernous space of New York’s Carnegie Hall after the audience has long left and a mere usher remains to take the stage and play alone for the cleaning crew.

Ruth had recounted just that story not long before she painted the notes of Mendelssohn in the air of her suite, followed by a lively rendition of Chopin’s Fantasie-Impromptu.

She spoke of her passion for music, which flowed from her organist mother and was nurtured by her father, who so loved his wife’s gift that he built a pipe organ in their home. Ruth was barely two when she began to play and by the time she was four, she was enrolled in Toronto’s Royal Conservatory of Music, where she would eventually study under Chilean composer Alberto Guerrero, who famously mentored Canadian Pianist Glenn Gould.

“Glenn would only come in occasionally, play for us and then walk out,” Ruth recalls with a smile. “He was not one to stay around and socialize.”

Music led Ruth through life: from the grand piano in her room and the pipe organ her father built in their home to the royal conservatory in Toronto to New York, where she studied and had that wonderful job at the world-famous venue.

“I enjoyed my time in New York because I had the best job a student could ask for,” she says. “I could hear all the concerts for free and, I must admit, an enjoyable thing for me was after everybody had gone home and Carnegie Hall was empty, I could go up on the stage and play for myself.”

It is easy to imagine a full house there just to see her.

Ruth would later travel through Europe as the pianist with the Elmer Iseler Singers, echoing wonderful music off the stone walls of ancient cathedrals, by Canadian standards. She then became the accompanist for the Toronto Childrens’ Chorus – a position she held for three decades, which again carried her around the world. After she married and had children, music would always be there, from small town Manitoba where she first settled with her husband and back to Toronto, where she remains today.

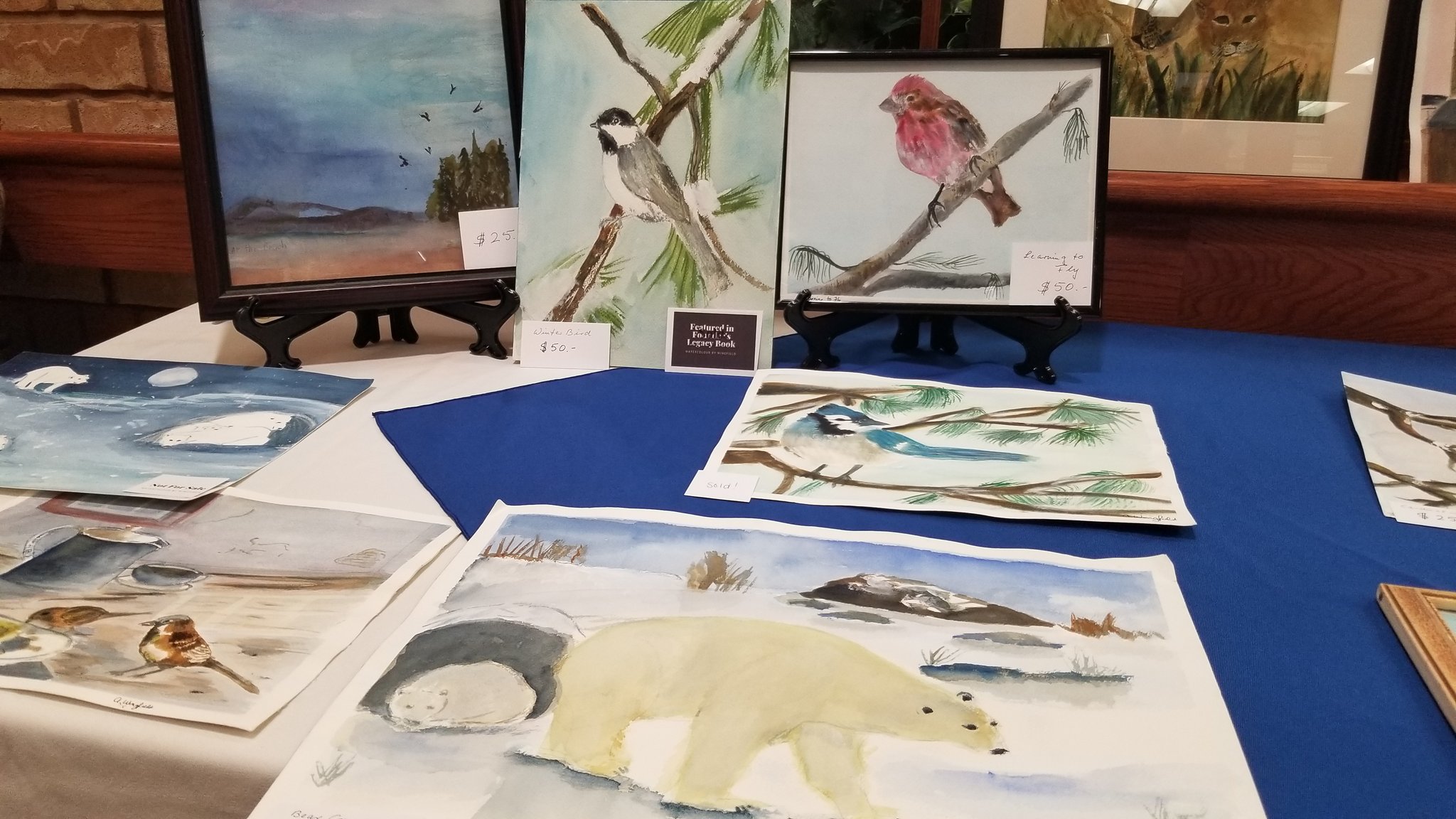

Her lengthy career as a choral accompanist led her to the other important path of her musical career as a distinguished and internationally-recognized composer of choral music, explains her daughter Deborah. She and her sisters “used to lie in bed as kids and could hear her working on new compositions at the piano late into the night,” Doborah says. “Despite the fact that she is no longer able to recall many of the pieces she has written, she enjoys listening to recordings and performances of her music, particularly when she has the musical score to follow.”

Deborah will often bring her violin to the Village when visiting and she and her mother will play together, for despite the faded memories, Ruth can read music just as anyone might read a book. “Mom will often say that her fingers work better than her brain, but I think her ‘music brain keeps up perfectly well when she’s at the piano,” says Deborah.

As Schlegel Villages closes the month of June with its virtual Pursuit of Passions event, Ruth’s story of passion for the piano resonates.

“Just getting completely involved in music is what I love most,” she says. “It just sort of takes over my whole body and I can feel the rhythm and the direction it’s going in. You can’t just sit at the piano with your fingers going and not involve the rest of your body; you have to feel right into the music.

“It has to be all through your system,” Ruth says.

As the final notes of Chopin fade off in her suite and Ruth’s eyes open, she leans back from the piano and one can see exactly what she means. Decades have passed since she was a girl in front of the black and white keys or the teenaged usher upon Carnegie’s stage, but the music still flows through Ruth’s system as fluidly as it did a lifetime ago.